Jim Collins, in "Good to Great," describes the flywheel effect as the cumulative effect of continuous effort put towards a goal.

The more you keep pushing, the faster that flywheel will eventually be turning.

Initially, it's quite slow, and you may wonder if it even makes a difference to push it. But then, over time, it will build momentum.

What I found most interesting about this analogy is the idea that when looking back, you can't identify a single push that was responsible for it to be spinning faster.

Some actions or activities in our lives might have more impact than others, but these more impactful activities often "stand on the shoulders of giants".

Learning From Mistakes

As Newton described, his groundbreaking work was not entirely groundbreaking because of him alone, but rather because he was building upon all that others had already discovered.

It's the same with our activities throughout our lives.

A setback, or an activity we might think of as pretty useless, might have shifted our perspective, preparing us for a truly impactful activity.

Maybe a business that we have started and failed with has taught us something useful, so that during our next attempt at starting something, we can overcome that same hurdle.

Each and every push on our life flywheel will not have the exact same impact, but the stronger ones will have been built up by a lot of the weaker ones.

A failure, in a way, is not slowing the flywheel, but it enables the next push to be even stronger.

In my piece about my struggles with building a personal finance app, I described how doing something that might seem pointless or wasted also contributes to learning.

That learning, just like the pushing of the flywheel, accumulates.

And more often than not, learning isn't what we remember it to be from school.

We don't just learn by reading books, attending classes or courses. We mostly learn by doing.

I'm trying to grow the presence of my site by improving SEO, which I do through a combination of reading and experimentation.

My personal finance app might never take off, but what I'll take away is how to approach building SEO, marketing, or selling. Or even more suitable, how NOT to do any of that, because last time it didn't work.

Ever since I first read Good to Great, I've found the flywheel analogy intriguing.

It's almost like, as long as you work towards a goal, you'll get something out of it. All you need is consistency. Don't stop and keep doing that thing.

That's easier said than done, though. What goal are we even pushing for?

What Flywheel Are You Pushing?

I don't think one should just do anything, but ever since writing this piece, I've also been thinking and reading a lot about what motivates and drives people.

For me, this is somewhat clear. I assume my love for surfing triggered it. I got obsessed with living in a different country (with waves).

That goal then morphed into being able to live wherever I want.

If you think through achieving such a goal, you see that you'd either need to be extremely flexible and find work wherever you want, financial independence, or a set of your own income streams.

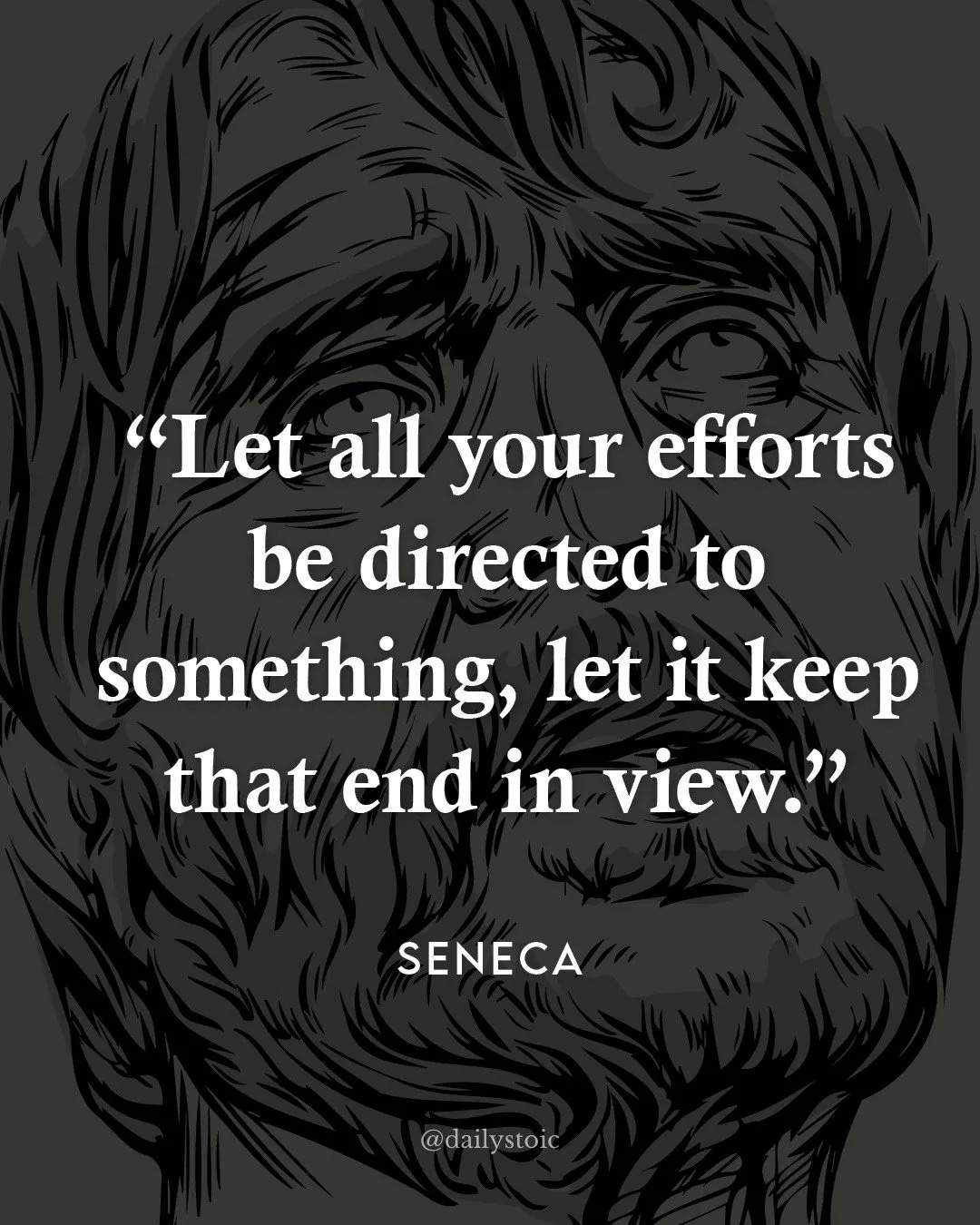

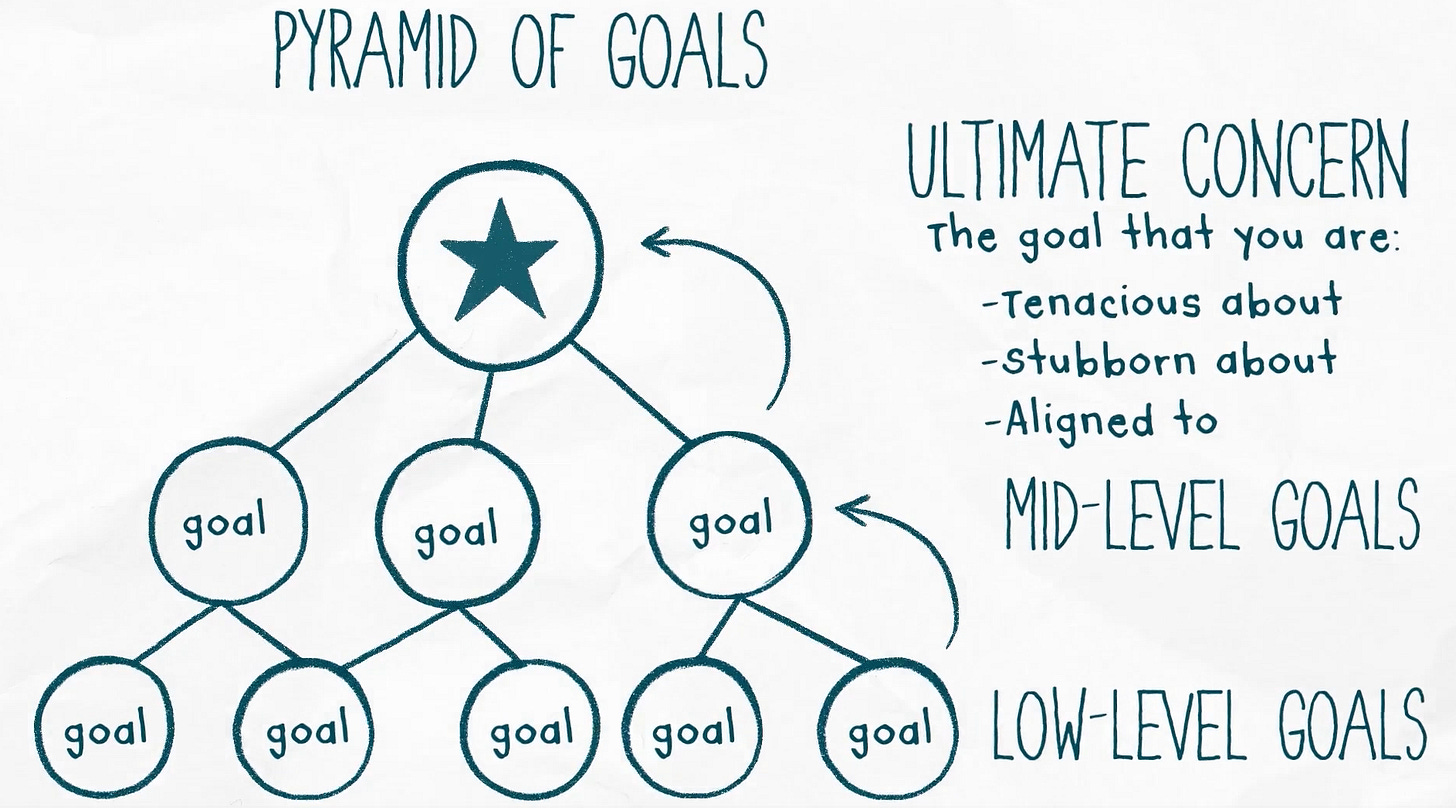

This is described as a pyramid of goals by Angela Duckworth in her book Grit.

(image from Angela Duckworth: Hierarchy of Goals)

Grit is a characteristic that drives some people to be extremely persistent in pursuing a goal over an extended period.

The ultimate concern she describes here could be my desire to live wherever I want.

That high-level goal has multiple hierarchical levels of lower-level goals, each with sub-goals that feed into it.

So for me, that might look like this:

Live wherever I want

1. Have a large enough runway to move and weather a storm.

2. Have a generalist skillset that enables me to find a job in case of emergency.

3. Have my own income stream via a business.

One of these lower-level goals can have more sub-level goals that ultimately break down into tasks to work on actively.

Sticking to my example:

Have my own income stream

1. Build up Substack so I might make money off of that someday.

2. Build up Expense Sorted so it might turn into something.

3. Find consulting clients that I can work for.

All of these subtasks align with my higher-level goal. The good thing about being aligned with those higher-level goals is that it motivates.

Not consciously in day-to-day life, but rather as a background process in your brain that compares your current activities with the overall goal that you have.

One might stray from that path for a while, but unless your goal changes, you will eventually recognise that you have gotten off the path and correct course.

The Failure Feedback Loop

Some of these tasks will fail. Perhaps Expense Sorted won't find product-market fit and will never gain traction.

Looking at my overarching goal, I might have wasted some time chasing down the wrong path, but I have learned some valuable skills.

Perhaps I was just lucky with my first startup. The second time, maybe I didn't communicate or sell it effectively, or perhaps my timing was off. Who knows.

Whatever it is, these attempts and the learning that comes with them all contribute to pushing our flywheel.

If Expense Sorted fails, I'll do something else under that branch of "Have my own income stream", but this time I'll be equipped with more learning.

Even though a sub-goal failed, work towards the highest goal continues, and new sub-goals emerge all the time.

Next time, pushing the flywheel, I'll be standing on all the lessons learned from the activities I have failed at.

How do we know what the goal is?

This has been extremely subtle for me, and my understanding of it has only developed over the last few years.

It was, however, always somewhere deep down.

Some might like goal setting by planning out what and where they want to be in the next five to ten years, and that can certainly help. The active process of thinking about this is often enough to get started.

The honest answer, though, is that I don't know.

It may require a great deal of introspection, a lot of self-reflection, and careful consideration of your life and what is truly important to you.

Goals might not need to be as strict as Angela Duckworth and the gritty people describe them. If you swap your higher-level goal after a couple of years, I guess that's totally fine as long as you keep pushing your flywheel of learning new skills.

Most skills you learn will be somewhat transferable.

Learning how to sell or negotiate is very generic, as well as knowing how to articulate things.

In many ways, simply being aware of the relationship between a higher goal and your day-to-day activities might get people thinking.