Scrolling through Twitter for thirty minutes or going for a thirty-minute run each produces dopamine. Yet both have a very different effect.

Seeing likes, messages, and short-form content is nice for the brain. Otherwise, we wouldn't all spend so much time doing it, and we wouldn't all be a little addicted to it.

Both activities tend to release dopamine. Anyone, however, who has ever achieved something that also took effort or required work knows that the dopamine from the work or effort hits very, very differently.

In a nutshell, here's the difference:

cheap dopamine: instant, passive, temporary, e.g., getting likes on Twitter.

earned dopamine: delayed, requires effort, lasting, e.g., improving fitness after working out for a year.

The earned dopamine goes deeper and lasts, but it also takes time to materialise, and that's a problem.

The Allure Of Cheap Dopamine

Historically, cheap dopamine wasn't so readily available. Our brains seemed to be wired for whatever you could find. If you find a blueberry bush in the woods, the dopamine created will lead to you remembering where it was because it felt so good. You likely also smashed through as many as you could. But being out in the woods 20,000 years ago wasn't without risk. Ask any grizzly bear.

Today, instant, cheap dopamine is everywhere. No risk, no effort required. You pay later, though.

In my early twenties, I spent a lot of time playing World of Warcraft. It was the greatest thing. I still think back sometimes and contemplate trying it out again. The feeling of levelling up, gearing up your character and then winning games against other players involved a lot of dopamine. It felt great in that moment. It was addictive.

But the moment you stopped, it felt bad, and you wanted to get back to it.

It had almost zero lasting impact, but I could be lazy and happy.

Only when zooming out, we will see that spending our time on working out, reading books, or learning any other useful skill has a far longer-lasting impact.

If you play World of Warcraft three times a week for four months, you don't have much to take away from it. If you spent that same time working out instead, even if you stopped, a lasting positive feeling would stay for much longer.

If you go for the cheap, short-lived dopamine, however, it might be nice in the moment, but you will not have that deep feeling of knowing how to do something or that deep feeling of being content because you have worked your way through challenges.

Compounding Cost

But why not just keep going on the cheap dopamine? It's free, easy, and makes me happy.

I remember back in my Uni days. I was working full-time and hitting uni in the evening. On the way home around 9, we'd stop at a burger joint to have dinner. After a couple of weeks, I felt terrible, didn't sleep well and also gained some weight.

It's the cheap dopamine hit of that salty fatty food, but the aftereffects compound and quickly influence other areas of our lives.

The short-lived pleasure of the burger was creating a long-term deficit in my well-being. The same is true for binge-watching Netflix all Sunday instead of taking a walk, or ordering takeout instead of learning to cook. It's a deal that feels good upfront, but leaves you poorer in the long run.

In investment terms, people talk about opportunity cost.

If you spent the time reading about investing, instead of watching Netflix, what would your life look like then?

By living off cheap dopamine, we are taking away from our potential to do something that creates lasting contentment and a sense of meaning.

Purpose and Guardrails

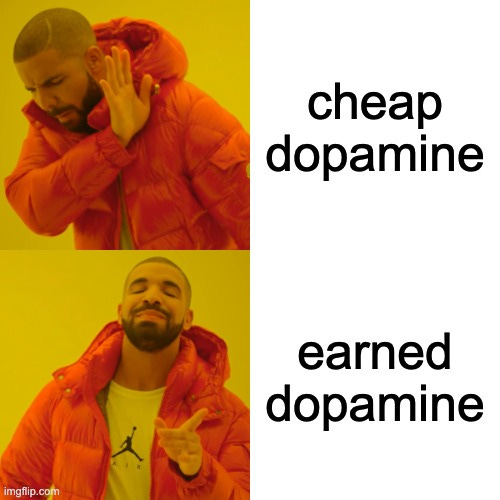

Knowing that cheap dopamine is a trap is a good start, but resisting it in the moment is a different story.

The answer isn't just more discipline. It seems to come down to two things: having a reason to bother (purpose) and the guardrails in place for when discipline and motivation go overboard.

Simply thinking about how good I will feel after the workout often isn't enough. To me, linking an activity to a higher-level goal (check out my deep dive here) is what can make the difference.

The chore of writing cold emails only becomes tolerable when I frame it as the direct alternative to returning to a corporate job I don't want. One choice moves me closer to freedom; the other moves me further away. That clarity helps.

That's the purpose of a higher-level goal.

But what if that framing fails and binge-watching YouTube becomes too tempting?

Here is where guardrails come in. Some people think I'm really disciplined, and I might be a little more than average, but I've also been building systems that help me when I'm not disciplined.

I'll smash through a bar of chocolate when I'm hungry, no problem. I just never have any at home.

I'll get distracted by YouTube, but use apps like Cold Turkey to block out periods of work and focus.

I didn't go for runs at all because it always took so long. Now I go two to three times a week by cutting down the time to just 30 minutes.

The Fisherman's Point

There's always a risk, when talking about this stuff, of sounding like the businessman in the old parable, telling the fisherman to work relentlessly now for a payoff that might come decades later.

That's not what this is aiming for. There is a difference. The fisherman lives in the moment and genuinely seems to be enjoying life. The fisherman isn't doomscrolling Twitter, TikTok or Instagram to get his dopamine. He seems to derive his happiness from being in the moment, enjoying time with friends.

The point is not to avoid pleasure, joy and happiness completely; it's distinguishing between cheap and earned dopamine and knowing where your contentment comes from.