We lived in a 120+ sqm house in Germany before we left for Singapore. Prior to the move, we visited Singapore and checked out a few places.

A 120+ sqm house was far too expensive in Singapore. We'd have to settle for a much smaller place.

So we started selling a few of our bigger items, such as our king-size bed, our big couch and our dining table. On top, we did a lot of decluttering of stuff we had accumulated over the years.

Despite all that, we still loaded up a 20ft container to the brim.

In Singapore, we noticed we weren't using most of the stuff we had brought, so we started selling things.

Even though we thought we had gotten rid of a lot of stuff when packing for our move to Sydney, we still filled more than half the 20-foot container.

Our journey to declutter continued until our next move. This time with just six bags!

How did we get from a container to a few bags? We accidentally became minimalists.

The Hidden Reality of Stuff

Why did we even accumulate so much stuff in the first place?

There is always a constant stream of stuff coming in.

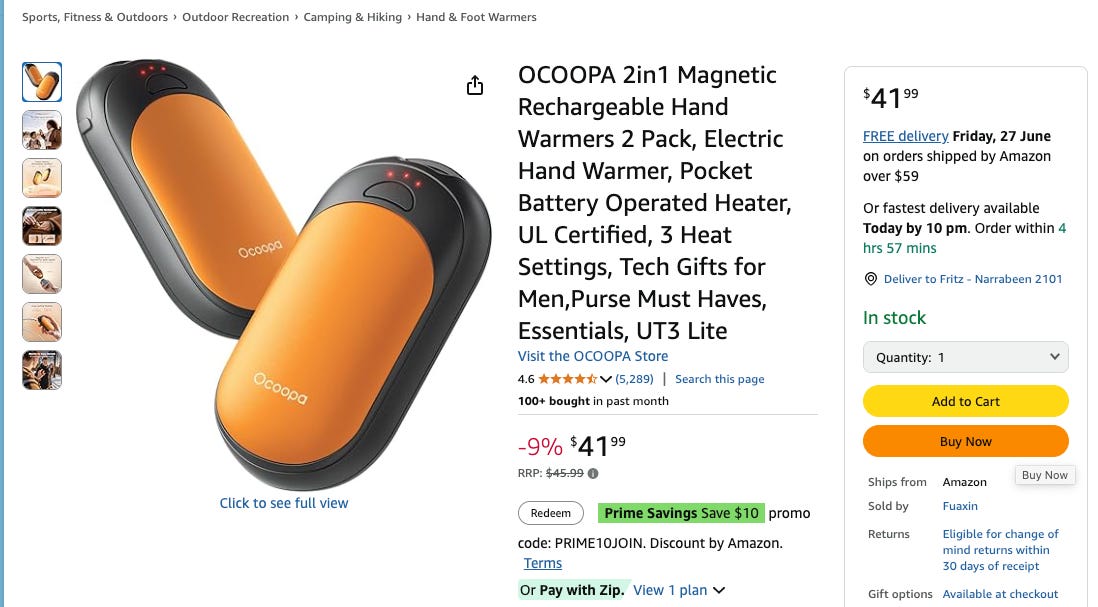

Going to the shops, ordering from Amazon, whatever it might be, it's gotten so easy to buy stuff that we do it almost every day.

Marketing, peer pressure, or simple boredom might be the reasons, and often, it happens unconsciously. We buy stuff without even noticing.

Not that we don't notice that we buy, but we don't notice the accumulation. It gets stored away somewhere in our house.

While buying stuff is easy, almost automatic, getting rid of it is not.

It's hard to separate from something that we already own. We've spent money on it, so we can't just give it away. What if we need it in the future?

Just like that, we'll accumulate vast amounts of stuff over the years.

For us, it was the move overseas that triggered taking inventory.

The size of our shipping container was limited, so we had to decide what to keep.

Most of the things we uncovered when prepping the move were things we had forgotten about, tucked away in boxes in the basement.

We hadn't used them for years and didn't even need them.

The accumulation of stuff happens unconsciously, and we hardly ever make a conscious effort to get rid of it, even if we don't need it.

What do we need?

You will have heard of minimalism, and like me, you might have an image in your mind of an empty room with a single chair or something similar.

I don't want to live like that, but like everything in life, there is a spectrum between that end and the end where you have a whole basement full of boxes you haven't touched in years.

We used a simple rule: if you haven't opened a box or used an item for more than half a year, chances are you won't use it again.

If space is not a problem, you don't need to bother decluttering; there's no point in throwing things away.

But if space is a problem and you move around or, worse of all, have forgotten about something and bought it again, then you have a problem.

You may buy stuff for the dopamine rush of the purchase, the feeling of newness itself.

From my experience, this is a false sensation of happiness that isn't sustainable.

Observe yourself after a purchase. The moment of buying feels great, unpacking and trying it out does, too, but more often than not, that's it. Your life often doesn't get any better by buying a new gadget.

What can you do about it?

The power of friction

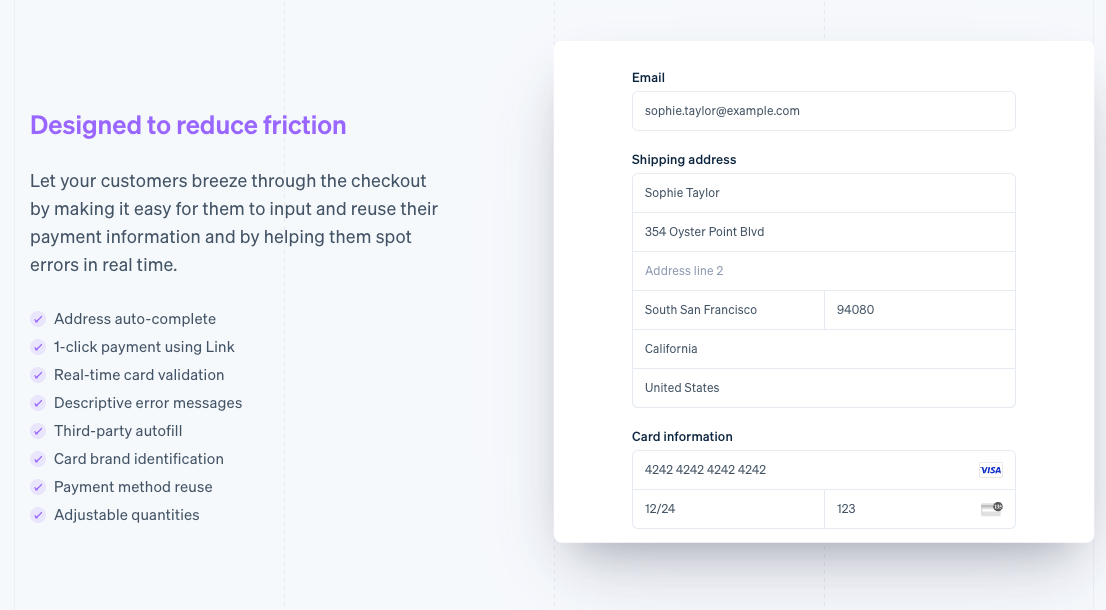

If you've built a webshop or sold pretty much anything, you know that a big part of successful sales is reducing friction. You want that purchase decision to be as easy as possible.

Amazon, etc., have perfected the checkout. It's a one-click purchase, where you don't even review the shopping cart; they just charge your credit card and ship.

What if you don't like it? No worries, free 30-day return policy!

They want you to buy it, store it at home, and forget about it.

Reintroducing friction, however, can help if you want to be more conscious about buying things.

You could buy stuff at a physical store, requiring you to drive there.

When we moved to Singapore, we stumbled into a different kind of friction—second-hand purchases.

We knew we wouldn't stay in Singapore forever, and we had just sold so much that we weren't keen to buy new stuff.

The second-hand market was great, so we bought much of what we needed that way.

Buying stuff from random people, picking it up at their place, and not having free shipping isn't easy. It's pure friction, and you'll certainly think twice about buying something.

Buying something second-hand also creates less emotional attachment; if you could buy it, you could sell it too.

Artificial friction could be introduced by simple rules, such as waiting a day before buying something.

I'm not so much interested in buying less simply to own less. It's more about being in control instead of running on autopilot.

Peer pressure seems to lead many people astray here. Often, a purchase can be motivated by other people owning something you don't.

Authenticity Inspires

IYKYK—we drink out of peanut butter jars, and it's not only practical (they are bigger) but also free.

My wife is usually a little embarrassed when we have guests over to serve them water out of peanut butter jars, but when she did so recently, the guests liked them and started collecting them too.

This is a nice example of how you may not want to reveal your true self, but doing so inspires others.

Peer pressure can sometimes drive people to do stuff they wouldn't otherwise do.

Our couch consists of two mattresses and a bunch of pillows. It's uncomfortable for us old folks to sit down and get up again, but the kids love it. If we cared more about what other people think, we'd probably buy a proper couch, but focusing more on what we need has taught us this.

Admittedly, having people over who don't know you can still be a little weird with our couch setup.

What Matters: Time Over Things

Focusing more on important stuff sounds like such a vague thing to say. What does that actually mean?

What is important to you is hard for anyone other than you to figure out.

To me, it's knowing that my kids ultimately don't care that much about a new toy. My son would always prefer to just go for a little stroll around the neighbourhood, checking out cars and diggers instead of buying him something new (he'd take a new toy, of course, but then wants me to play with that toy together with him). So why not just give him time straight away?

Another weird paradox is our current living situation. We have a super nice townhouse that is 2 minutes' walk from the beach, and we like it and enjoy living here. But looking back at our time living in a bus travelling up and down the coast, we felt happier. The small space and simple life led to fewer commitments and more time outside.

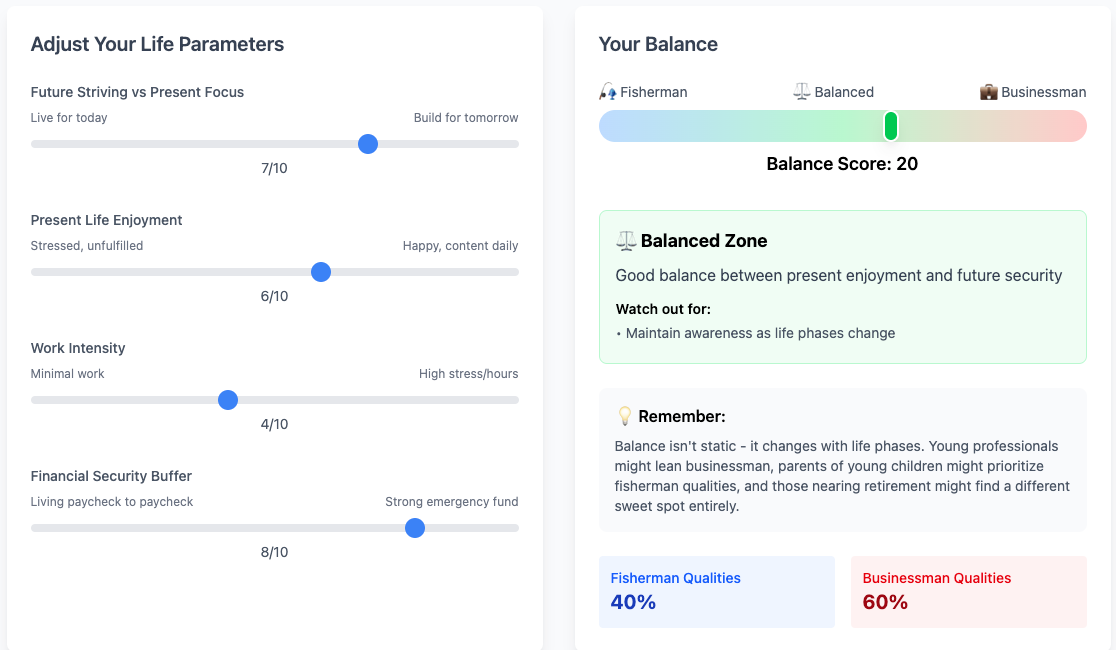

A simpler life means more time for relationships and hobbies and less stress. It is what the fisherman has known all along.

The Fisherman's Dilemma: Why 'Enough' Is the Hardest Financial Number to Find

An enterprising tourist encounters a contented fisherman dozing by his boat. The tourist, embodying a capitalistic mindset, proceeds to lecture the fisherman on how he could expand his fishing operation—working longer, buying more boats, hiring staff, building a cannery, and eventually becoming wealthy enough to retire and enjoy a relaxed life by the se…

Like I keep saying, everyone is different, but upon introspection, we learn that more things often aren't the solution we hoped they would be.

Financial Minimalism

This same concept applies to your finances.

Most startups work like this: You start with an idea and a limited amount of cash while making no money. The goal is to make money before the cash reserve runs out. You could go all in and spend it all quickly, betting on making money in a certain way, or you can take a more considerate approach and keep the "burn rate" under control.

This means you are careful with hiring or stay flexible enough to downsize the team if needed.

In this fight for survival, startups are often minimalistic by default (working from a garage).

Applied to personal finance, this thought experiment can give a great feeling of safety. I might be renting a townhouse by the beach right now, but I could downsize anytime, move back into a bus, and live a cheap life.

That's an extreme example, but minimalism from a financial lens means that one shouldn't get too comfy and used to one's expenses and general lifestyle bloat.

Financial minimalism here isn't about deprivation, just as I don't like to live like a hermit in other areas of my life, but I want options, I want to be flexible (perhaps to say f-you).

Fuck you money doesn’t mean you need to be rich

After clashing with my co-workers at my corporate job last year, I decided to pull the trigger and quit. Did I have a new job? No.

Eating out every day because you don't know how to cook your own food could be a more basic example. Cooking at home is generally healthier and cheaper than ordering food every day, but if you get too used to ordering, you'll have to wean yourself off if things get rough.

An Ongoing Practice

Minimalism to me isn't an empty house and only owning one pair of shoes.

It's being aware that stuff you might not need silently creeps into your household while you spend your hard-earned money. A little friction can help.

It's focusing on what we need. This can get quite philosophical, but think about which of your habits have consistently delivered a better feeling than buying stuff. Maybe exercise? A better diet? Good relationships? Time for yourself?

It's the courage to live authentically and free of peer pressure. There is genuine value in being yourself. If you pull it off, more people than you expect will be inspired rather than put off.

It's the ability to downscale if you need to because you can adapt and still live a good life without all that stuff.

You don't need to move across the world to start. You just need the courage to ask yourself what truly matters, and the honesty to act on the answer, taking one step at a time.